I am a researcher, academic, and consultant specializing in radicalization, de-radicalization, and counter-terrorism policy.

I am a researcher, academic, and consultant specializing in radicalization, de-radicalization, and counter-terrorism policy.

Since the 9/11 attacks, governments in the West have primarily attempted to manage the risks associated with terrorism through kinetic and legislative means. However, those are arguably reactive rather than proactive measures and do little to stem the problem. Moreover, the use of hard power mechanisms by Western governments is not only extremely expensive, it has in many instances alienated communities and exacerbated the problem, rather than minimize it.

Particularly in Europe, governments often view ‘radicalization’ as the core problem and assess that it, and the threat it poses, must be stopped. Some have attempted to employ preventative measures, but the ability to build meaningful resiliency against the dissatisfaction and disaffection leading to radicalized political thought has had little success. Thus, the motivation behind my work is to develop new primary data to enhance understanding in what has become a very politicized, dynamic, and misunderstood environment. In my view, the only way to do that is to interact with individuals pejoratively labeled as radicalized extremists, and terrorists.

I spent my first career (29 years) working as a firefighter and paramedic in southern California. During the last fourteen years of my career (1996-2009), I coordinated our city’s efforts against terrorism and for several years served as the Emergency Services Coordinator where I was engaged in wide scale emergency planning. The work I was doing on terrorism rapidly expanded to the region, state, nation, and ultimately international levels.

Before I left the fire service, I made numerous trips and spent considerable time in Israel, Palestine, and Northern Ireland working along-side police, fire, EMS, and military resources in those countries. As a practitioner it was important to not only see what they did and how they did it, but to understand why they did what they did. However, I quickly realized that view only provided part of the picture. To wholly understand why people radicalized and engaged in violence, I began interacting with those that were considered terrorists by those same governments. Those differing perspectives are what continues to drive me today.

When I left the fire service, I intimately understood the government top down policy and practitioner environments, but I wanted to know more about how and why individuals radicalized and the effects that government led counter-terrorism policies and strategies had on them. To fully comprehend the bottom up perspective, I completed a PhD on the subject which involved an extensive ethnographic exploration of how mainstream Muslims and the radical fringe react to counter-terrorism policy in the UK.

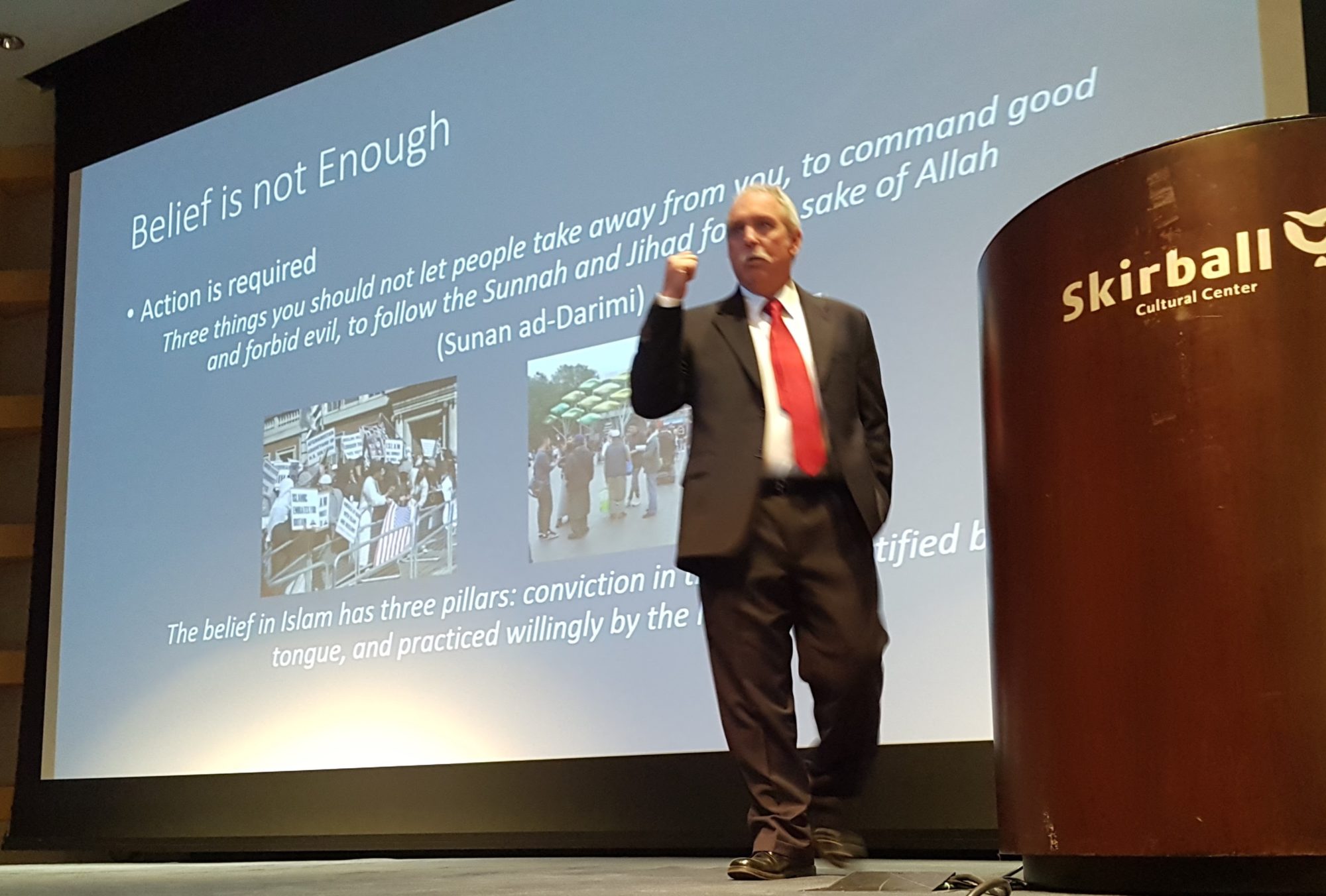

The UK has a large Muslim population and is home to what many would consider extremist and radicalized Islamist groups. Unlike most researchers who never interact, or at best have minimal interaction with the individuals they claim to have expertise about, I chose to embed myself with them. Since 2010. I have engaged with and regularly interact with individuals who have been convicted of terrorism related offenses, are on or have been on Terrorism Prevention and Investigatory Measures (formerly Control Orders), former Guantanamo Bay detainees, and others the government considers radicalized extremists and terrorists, many of which have gone on to fight with the Islamic State. I also interact with individuals who serve as core Islamist ideologues in Europe, and the Middle East so that the root issues and arguments are understood.

Governments are driven by the belief that radicalisation is the main source of threat. To minimize that threat, they have engaged in various efforts to ‘de-radicalize’ those that are ‘at risk’ of being radicalized, those about to be released from prison, and those that are believed to be ‘involved in terrorism’ and placed on highly restrictive administrative orders (TPIM’s). My work on radicalisation and the individuals and groups that I’ve studied led naturally to doing work on ‘de-radicalisation’ as many of the individuals I’ve interacted with have been subjected to such initiatives. To be sure, de-radicalization is not radicalization in reverse and measuring success is not about returning the individual to his/her pre-radical state of mind.

By far, the available research on de-radicalisation has primarily occurred in prisons. However, the institutionalized control and quid pro quo relationship that exists in prison raises several questions about how that research can be applied outside of that environment. In my assessment, the conclusions derived from prison-based studies rarely make for reliable indicators of post release behavior. To answer some of the lingering questions, I’ve focused on researching the post-release environment and have completed two major studies on that subject.

The work that I do primarily focuses on bridging the academic/practitioner divide. Arguably, more securitization and additional hard power mechanisms is not the answer. The approach utilized for the past two decades has proven to be costly, ineffective, and often counter-productive. The recent rise of the Islamic State and the popularity it enjoyed, is clear evidence that a new approach is needed. I advocate for a more holistic approach based on a broader understanding of the issues so that risk can be reduced. To that end, I provide academically rigorous but pragmatic insights, assessments, and education to policy makers and practitioners. I offer real world perspectives and solutions to real world problems.

Get in touch for more information.